There

have been many amazing experiences since I have started researching

mine and Margaret’s family tree (well, it’s essentially Tom, Sam and

Max’s family tree). Recently, I’ve been looking at my mother’s mother’s

father’s ancestors; family name Burrows, who came from

Norfolk and, in particular from a small village called Burston just

north east of Diss.

We visited Burston in July (as regular readers will know) and had a look around and since then, I’ve done some more internet research, found additional family members and unearthed various skeletons. I think we were all amused to find that we had a relative called Zachariah Burrows - it is an impressive name. He’s my 3 x great grandfather (so five generations back) and was born in the late 18th Century. He and his wife Ann had seven children, including my great, great grandfather Job and also a son named Zachariah after his father.

I got a trace of Zachariah junior having become an American citizen in 1868 (aged 53). I wasn’t absolutely sure that it was him and I was also faced with having to pay a higher subscription on Ancestry.com to get access to overseas records. I’d taken the view that there was plenty of research in the UK to get on with but then, last weekend, Ancestry had a free weekend for US emigration records, so I spent some time looking up relatives who had emigrated, including Zachariah.

I was able to confirm very quickly that it was my great, great grandfather’s elder brother. The records showed he’d become an American citizen in 1868 and has settled in Rock Bluffs, Nebraska but had died soon afterwards in Plattsmouth. I was also able to find some people in America who also had Zachariah in their family tree, so I e-mailed them to say that we might be (very) distant cousins and were they interested in the information I had about the Burston Burrows?

One of the really nice things about ancestry research is finding people looking at the same people and sharing information you have. Ann Seymour (nee Burrows) from the USA sent me this reply the same day:

What a wonderful surprise to see this message and to share your tree. One of my mysteries is why my great great-grandfather, Zachariah, went to Canada West (present day Ontario) where he met Hannah Woodward. I am assuming that because there were 7 children maybe it became necessary to send some children there. I have an original letter dated Nov. 11, 1843 that Ann wrote Zachariah while he was in Canada and the letter mentions Job, I would be happy to send you a copy.

Zachariah eventually went to Michigan where William Perry was born. Then it was on to Nebraska where my grandfather, Charles Perry, was born.

My father, Charles Myers Burrows, died in 1996 in Lawrence, KS. He was born in Ottawa, KS where he met my mother. Mom (Beverly Jean Pope) was born in Ottawa and is still alive at 92 years. She lives in Lawrence, KS.

Thank you again for sending the email. My dream one day is to travel to England to find Burston parish and walk the ground where my ancestors lived.

So Zachariah had gone to Canada at first and had then moved into the US some years later. He’d married Hannah Woodward, originally from New York and almost certainly of British origin herself. Zachariah had escaped agricultural work in Norfolk to make a new life in Canada and then America, thousands of miles further west, in Nebraska. Sadly, he died aged 54, quite a young man compared to the other Burrows.

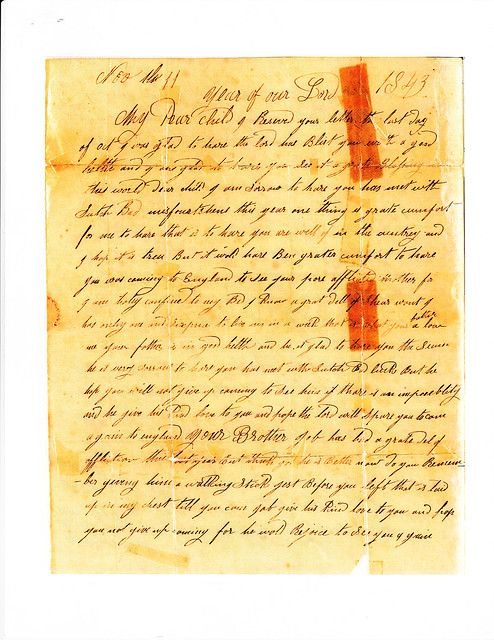

Ann sent me the letter written by my great, great, great grandmother over 160 years ago. I’ve pasted copies below and the high-res version (which is very clear) is on Flickr - just follow the links. This is the transcript of the letter, there are one or two words that I haven’t quite got. I haven’t changed any of the spelling or punctuation and it’s clearly written in the vernacular and by someone not used to writing regularly:

To Mr Zachariah Burrows

Clear vill Western district

Uper Canada

North Amarica

Page 1

November 11

Year of our Lord 1843

My Dear child I Reseved your letter the last day of oct I was glad to hare the lord has Blist you with a good helth and I are glad to hare you see it a grate Blefing in this world Dear child I am sorrow to hare you has met with Sutch Bad misfortshens this year one thing of grate comfort for me to hare that is to hare you are well of in the country and I hope it is true But it will have Been grater comfort to hare you was coming to England to see your pore afflicted mother for I am holy confined to my Bed I know a grat dell of Shear want I has only one and sixpence to live on in a week that is what your father allows your father is in good health and he is glad to hare you the same he is very sorrow to hare you has meet with Sutch Bad luck but he hop you will not give up coming to see him if there is an impossibility and he give his kind love to you and hope the lord will spare you to come again to England your Brother Job has had a grate lot of affliction this last year But thank god he is Better now Do you Remember giving him a walking Stick just Before you left that is laid up in my chest till you come Job give his kind love to you and hop you not give up coming for he will Rejoice to see you a gain

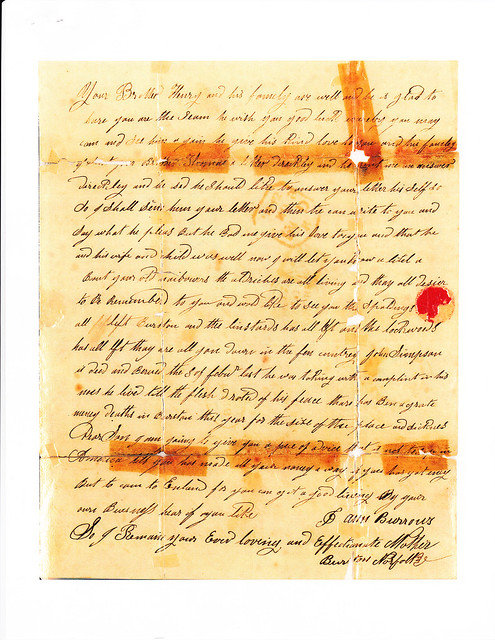

Page 2

Your Brother Henry and his family are well and he is glad to hare you are the seam he wish you good luck wareby you may cam and see him a gain he give his kind love to you and his family I sent your Brother Thomas a letter direckley and he sent me an answer direckley and he sed he should like to answer your letter his self so so I shall send him your letter and then he can write to you and say what he pleas But he Bad me give his love to you and that he and his wife and child was well now I will let you know a litel a Bout your old neighbours the aldriches are all living and they all desier to be Remembered to you and would like to see you the Spaldings all hef left Burston and the linstards has all left and the lockwoods has all left thay are all gon down in the fen country John Simpson is deed an Buried the 5 of febury last he was taking with a complint in his noes he lived till the flesh droted of his feace thare has Bin a grate many deaths in Burston this year for the size of the place and sicknes Dear Son I am going to give you a piece of advice that is not to stay in Amarica till you has made all your money a way if you has got may But to cam to England for you can get a good living By your own Bussinefs hear if you like

Ann Burrows

So I Remain your Ever loving and Effectionate Mother

Burston Norfolk

We visited Burston in July (as regular readers will know) and had a look around and since then, I’ve done some more internet research, found additional family members and unearthed various skeletons. I think we were all amused to find that we had a relative called Zachariah Burrows - it is an impressive name. He’s my 3 x great grandfather (so five generations back) and was born in the late 18th Century. He and his wife Ann had seven children, including my great, great grandfather Job and also a son named Zachariah after his father.

|

| Zachariah Burrows - part of the Great Migration |

I was able to confirm very quickly that it was my great, great grandfather’s elder brother. The records showed he’d become an American citizen in 1868 and has settled in Rock Bluffs, Nebraska but had died soon afterwards in Plattsmouth. I was also able to find some people in America who also had Zachariah in their family tree, so I e-mailed them to say that we might be (very) distant cousins and were they interested in the information I had about the Burston Burrows?

One of the really nice things about ancestry research is finding people looking at the same people and sharing information you have. Ann Seymour (nee Burrows) from the USA sent me this reply the same day:

What a wonderful surprise to see this message and to share your tree. One of my mysteries is why my great great-grandfather, Zachariah, went to Canada West (present day Ontario) where he met Hannah Woodward. I am assuming that because there were 7 children maybe it became necessary to send some children there. I have an original letter dated Nov. 11, 1843 that Ann wrote Zachariah while he was in Canada and the letter mentions Job, I would be happy to send you a copy.

Zachariah eventually went to Michigan where William Perry was born. Then it was on to Nebraska where my grandfather, Charles Perry, was born.

My father, Charles Myers Burrows, died in 1996 in Lawrence, KS. He was born in Ottawa, KS where he met my mother. Mom (Beverly Jean Pope) was born in Ottawa and is still alive at 92 years. She lives in Lawrence, KS.

Thank you again for sending the email. My dream one day is to travel to England to find Burston parish and walk the ground where my ancestors lived.

So Zachariah had gone to Canada at first and had then moved into the US some years later. He’d married Hannah Woodward, originally from New York and almost certainly of British origin herself. Zachariah had escaped agricultural work in Norfolk to make a new life in Canada and then America, thousands of miles further west, in Nebraska. Sadly, he died aged 54, quite a young man compared to the other Burrows.

Ann sent me the letter written by my great, great, great grandmother over 160 years ago. I’ve pasted copies below and the high-res version (which is very clear) is on Flickr - just follow the links. This is the transcript of the letter, there are one or two words that I haven’t quite got. I haven’t changed any of the spelling or punctuation and it’s clearly written in the vernacular and by someone not used to writing regularly:

To Mr Zachariah Burrows

Clear vill Western district

Uper Canada

North Amarica

Page 1

November 11

Year of our Lord 1843

My Dear child I Reseved your letter the last day of oct I was glad to hare the lord has Blist you with a good helth and I are glad to hare you see it a grate Blefing in this world Dear child I am sorrow to hare you has met with Sutch Bad misfortshens this year one thing of grate comfort for me to hare that is to hare you are well of in the country and I hope it is true But it will have Been grater comfort to hare you was coming to England to see your pore afflicted mother for I am holy confined to my Bed I know a grat dell of Shear want I has only one and sixpence to live on in a week that is what your father allows your father is in good health and he is glad to hare you the same he is very sorrow to hare you has meet with Sutch Bad luck but he hop you will not give up coming to see him if there is an impossibility and he give his kind love to you and hope the lord will spare you to come again to England your Brother Job has had a grate lot of affliction this last year But thank god he is Better now Do you Remember giving him a walking Stick just Before you left that is laid up in my chest till you come Job give his kind love to you and hop you not give up coming for he will Rejoice to see you a gain

Page 2

Your Brother Henry and his family are well and he is glad to hare you are the seam he wish you good luck wareby you may cam and see him a gain he give his kind love to you and his family I sent your Brother Thomas a letter direckley and he sent me an answer direckley and he sed he should like to answer your letter his self so so I shall send him your letter and then he can write to you and say what he pleas But he Bad me give his love to you and that he and his wife and child was well now I will let you know a litel a Bout your old neighbours the aldriches are all living and they all desier to be Remembered to you and would like to see you the Spaldings all hef left Burston and the linstards has all left and the lockwoods has all left thay are all gon down in the fen country John Simpson is deed an Buried the 5 of febury last he was taking with a complint in his noes he lived till the flesh droted of his feace thare has Bin a grate many deaths in Burston this year for the size of the place and sicknes Dear Son I am going to give you a piece of advice that is not to stay in Amarica till you has made all your money a way if you has got may But to cam to England for you can get a good living By your own Bussinefs hear if you like

Ann Burrows

So I Remain your Ever loving and Effectionate Mother

Burston Norfolk

The

envelope is postmarked Diss, also marked ”More to Pay” and postmarked

in Canada Dec 23/43. It was written on November 11, 1843, so 42 days to

get there. Clearville is in Ontario between Toronto and Detroit on the

north shore of Lake Erie. It looks to me (although this is conjecture)

that when Zachariah was settled in Canada, he wrote to his family back in

Burston. It’s not clear why he went, it seems he may have had some misfortune, but these were hard times working on the land and Ann (his mother) has a long list of grumbles, complaints and misfortune.

I thought when I first saw the letter, which has very neat handwriting, that it wouldn’t have been written by Ann. When she was married in 1806, she had made her mark in the parish register, so I had assumed that she was unable to read or write. I didn’t see how, with seven children surviving and clearly a pretty hard working life, that she would have been able to have learned to write. Having read the letter, I’m pretty sure that she had.

It’s actually a very poignant letter and, as a parent, it’s very easy for me to put myself in her shoes. Her concerns are health, having enough money and seeing her son again (she’s desperate that he comes to England to see her). I’m also interested to see that she mentions my great, great grandfather Job, who hasn’t been in the best of health, Job would have been only 24 in 1843 and was not married. I don’t know when Ann died, but I know that she and her husband Zachariah were living with Job in Burston in 1851 and Zachariah (senior) lived to the age of 79.

I was interested in how the letter would have been sent to Canada. The Penny Post was established in England in 1840 and you could send a letter anywhere in Great Britain for 1d (about 0.45p). Sending a letter to Canada would have been much more involved. Until 1845 the carriage of mail overseas was the responsibility of the Admiralty. It was privatised after that and companies could bid for the contracts, with ships carrying the RMS prefix (including RMS Titanic). So this letter would have been carried across the Atlantic by Admiralty ship, probably a fast sloop, but certainly under sail, and then overland to Clearville. The St Lawrence River (main route to the Great Lakes) would be icebound in December, so it must have gone overland. It would have been quite a journey and the fact that the letter survived all these years is a testament to how much it must have meant to Zachariah to have a little piece of home.

Zachariah junior moved to Canada at a time of mass emigration. Some 800,000 people left Britain for Canada in the 35 years from 1815. It’s a hugely significant event in the history of Canada and basically imposed a Britishness on the culture of the country that’s still apparent today. It’s called the Great Migration. Many emigrants would have been Scottish or Irish, but there were plenty of poor English people seeking a better life too. As mechanisation increased in the countryside, fewer people were needed to work the land and many traditional industries were shrinking or disappearing. The Norfolk weaving industry basically disappeared in the first half of the 19th century and Zachariah senior, who was described as a weaver as his children were being born is an agricultural labourer as he moves into old age. I have two branches of my family from Norfolk - the Burrows on my mother’s side and the Mitchells on my father’s. A couple of members of the Mitchell family also emigrated to Canada around this time.

I did wonder how the letter had got from Diss to Upper Canada and, indeed, how Zachariah had made the journey. His journey would not have been as fast (or comfortable) as the letter. I’ve not been able to find him on any passenger lists, but he would almost certainly have gone by sail as the first steam paddle-wheel ships were not really active until The Great Western in 1838 but they were expensive and a rarity and the first screw-driven ship (the SS Great Britain) was not launched until 1843. Sail was still the main means of propulsion for another 30 years after Zachariah made the crossing. London was a major departure point and it’s more likely that Zachariah sailed from there rather than Bristol or Liverpool as it would have been the nearest major port to Norfolk and Suffolk. Ships registered as sailing for Canada in the 1840s are almost all around 300-500 tons, whereas the steamships (few as they were) all weighed in at much more than that. The Great Western was 1750 tons and the SS Great Britain was 3675 tons.

So my best guess is that Zachariah made his way to London and embarked for Canada. He would probably have paid for his passage and would have gone in a small sailing ship across the Atlantic. There’s an excellent website called Norway Heritage which is aimed at helping Norwegians in America and Canada discover more about their ancestors. It describes conditions on board ship.

Passengers would have travelled steerage (nothing to do with being above the rudder, the term was used for people travelling without a cabin, ie camped out on a lower deck with perhaps bunks or canvas sheets between and everyone claiming their own little space. These ships were not purpose-built for passengers and people would have been carried below deck, but able to go onto the deck for fresh air when the weather was fine. Ventilation and light was through hatches, which would have been closed in bad weather, so the air would have quickly become very unpleasant. Typhoid, cholera and dysentery would be major killers and children travelling with their parents would have been especially vulnerable. Norway Heritage puts the death rate at four per cent in transit and I guess it would be similar among British emigrants. Average crossing time was 50 days, but could take two weeks longer in bad weather. Many ships, having made the crossing, were quarantined on Grosse Isle in the St Lawrence River to prevent diseases being carried into the country.

Despite his mother’s pleas, Zachariah didn’t come to England. In 1848, he married Hannah Woodward (from New York) in Clearville and in the next 20 years, they moved west to Michigan in the USA and then to Nebraska, across the Missouri River. Nebraska was just being opened up for settlement and by 1867 had enough people to apply for statehood. It’s the 37th State in the USA and Zachariah (from Burston in Norfolk) was part of its history.

I thought when I first saw the letter, which has very neat handwriting, that it wouldn’t have been written by Ann. When she was married in 1806, she had made her mark in the parish register, so I had assumed that she was unable to read or write. I didn’t see how, with seven children surviving and clearly a pretty hard working life, that she would have been able to have learned to write. Having read the letter, I’m pretty sure that she had.

It’s actually a very poignant letter and, as a parent, it’s very easy for me to put myself in her shoes. Her concerns are health, having enough money and seeing her son again (she’s desperate that he comes to England to see her). I’m also interested to see that she mentions my great, great grandfather Job, who hasn’t been in the best of health, Job would have been only 24 in 1843 and was not married. I don’t know when Ann died, but I know that she and her husband Zachariah were living with Job in Burston in 1851 and Zachariah (senior) lived to the age of 79.

I was interested in how the letter would have been sent to Canada. The Penny Post was established in England in 1840 and you could send a letter anywhere in Great Britain for 1d (about 0.45p). Sending a letter to Canada would have been much more involved. Until 1845 the carriage of mail overseas was the responsibility of the Admiralty. It was privatised after that and companies could bid for the contracts, with ships carrying the RMS prefix (including RMS Titanic). So this letter would have been carried across the Atlantic by Admiralty ship, probably a fast sloop, but certainly under sail, and then overland to Clearville. The St Lawrence River (main route to the Great Lakes) would be icebound in December, so it must have gone overland. It would have been quite a journey and the fact that the letter survived all these years is a testament to how much it must have meant to Zachariah to have a little piece of home.

Zachariah junior moved to Canada at a time of mass emigration. Some 800,000 people left Britain for Canada in the 35 years from 1815. It’s a hugely significant event in the history of Canada and basically imposed a Britishness on the culture of the country that’s still apparent today. It’s called the Great Migration. Many emigrants would have been Scottish or Irish, but there were plenty of poor English people seeking a better life too. As mechanisation increased in the countryside, fewer people were needed to work the land and many traditional industries were shrinking or disappearing. The Norfolk weaving industry basically disappeared in the first half of the 19th century and Zachariah senior, who was described as a weaver as his children were being born is an agricultural labourer as he moves into old age. I have two branches of my family from Norfolk - the Burrows on my mother’s side and the Mitchells on my father’s. A couple of members of the Mitchell family also emigrated to Canada around this time.

I did wonder how the letter had got from Diss to Upper Canada and, indeed, how Zachariah had made the journey. His journey would not have been as fast (or comfortable) as the letter. I’ve not been able to find him on any passenger lists, but he would almost certainly have gone by sail as the first steam paddle-wheel ships were not really active until The Great Western in 1838 but they were expensive and a rarity and the first screw-driven ship (the SS Great Britain) was not launched until 1843. Sail was still the main means of propulsion for another 30 years after Zachariah made the crossing. London was a major departure point and it’s more likely that Zachariah sailed from there rather than Bristol or Liverpool as it would have been the nearest major port to Norfolk and Suffolk. Ships registered as sailing for Canada in the 1840s are almost all around 300-500 tons, whereas the steamships (few as they were) all weighed in at much more than that. The Great Western was 1750 tons and the SS Great Britain was 3675 tons.

So my best guess is that Zachariah made his way to London and embarked for Canada. He would probably have paid for his passage and would have gone in a small sailing ship across the Atlantic. There’s an excellent website called Norway Heritage which is aimed at helping Norwegians in America and Canada discover more about their ancestors. It describes conditions on board ship.

Passengers would have travelled steerage (nothing to do with being above the rudder, the term was used for people travelling without a cabin, ie camped out on a lower deck with perhaps bunks or canvas sheets between and everyone claiming their own little space. These ships were not purpose-built for passengers and people would have been carried below deck, but able to go onto the deck for fresh air when the weather was fine. Ventilation and light was through hatches, which would have been closed in bad weather, so the air would have quickly become very unpleasant. Typhoid, cholera and dysentery would be major killers and children travelling with their parents would have been especially vulnerable. Norway Heritage puts the death rate at four per cent in transit and I guess it would be similar among British emigrants. Average crossing time was 50 days, but could take two weeks longer in bad weather. Many ships, having made the crossing, were quarantined on Grosse Isle in the St Lawrence River to prevent diseases being carried into the country.

Despite his mother’s pleas, Zachariah didn’t come to England. In 1848, he married Hannah Woodward (from New York) in Clearville and in the next 20 years, they moved west to Michigan in the USA and then to Nebraska, across the Missouri River. Nebraska was just being opened up for settlement and by 1867 had enough people to apply for statehood. It’s the 37th State in the USA and Zachariah (from Burston in Norfolk) was part of its history.

|

| The envelope is postmarked Diss |

Message from Margaret. I have still not got a handle on posting properly. I thought this was your best essay to date. I feared for poor old Ann, Zachariah's mum, as she tormented herself with the knowledge that her son was so far removed from her. It is easy in this communication friendly age to wonder at the dismay that distance meant to a loved one, but knowing how long a letter took to be delivered across the world is a powerful indicator.

ReplyDelete